I recently asked you, my beloved Darklings, if you would like me to do an essay on Eastern storytelling traditions as opposed to Western.

The support for this was overwhelming. Three of you said, yes.

Let’s begin.

Hakawati, is the Arabic tradition of story telling wherein each story must have…

Unfallen Darklings: Uh, Cataline that wasn’t the story structure we were interested in.

Dark Herald: I’m getting there. Don’t be a pest about it.

…and teach a moral lesson. I suspect this tradition is more Middle-Eastern than specifically Arabian because the story of Jonah fits perfectly within its structure.

Jonah’s story is rather unsatisfying to a Westerners who are used to a 3 Act story structure.

Jonah is ordered by God to go to Nineveh, the capital of the Assyrian Empire, and deliver a command from Him to stop sinning. Jonah, like all of his people, (as well as everyone else who had come into contact with Assyria), wants them all dead. So he refused to deliver God’s message and ran away to sea. A terrible storm came up while the ship was at sea and the crew drew lots to see who was to be sacrificed to appease the waters. The never-lucky Jonah lost and was chucked over the side. God sent a whale to swallow Jonah. Jonah repented and God had the whale spit, Jonah, on to a shoreline that had decent access to Nineveh. Jonah delivered the message to the hated Assyrians and then went to a nearby hill to watch God’s wrath descend on Nineveh.

And it promptly didn’t.

The End.

When I was in Sunday school the whale part of the story was the only thing that our teacher concentrated on. Mostly because a giant whale story would keep squirming seven-year-olds occupied while their parents had coffee and donuts after the service. It worked because that part of the story was the closest thing that conformed to the western idea of the three-act story structure with an introduction, an inciting incident, rising tension, climax, and then denouement.

The original purpose of the story however wasn’t to entertain, it was to teach.

The dominant religion in any area strongly influences that area’s story-telling traditions and story-structures.

Christianity has been the dominant religion in the West for the past 1,500 years or so. Give or take a few centuries depending on your location. Conflict is central to the faith. If you are a Christian, you are fighting Satan. If you fail at the fight you go to Hell. Win that fight and self-improvement will occur but it is a side-effect, not the goal. The goal is salvation and you don’t have to be the wisest of the wise in order to saved.

Buddhism is the dominant religion in East Asia. Buddhism at its center is self-improvement for its own sake. There is no conflict driving it forward. If you screwup in this life you slide down the ladder into a lower form of life. Be that a lower caste, a woman, all the way down to animals and insects. Improve yourself enough and you will achieve Enlightenment. And not have to be reborn into the world of suffering and desire anymore. But there is no conflict in this endeavor other than the self-conflict of Man Against Himself.

In Buddhism you absolutely have to be wisest of the wise. Achievement is a requirement to reach Nirvana, and this has influenced all aspects of their societies. Especially with regards to storytelling and it’s concomitant tropes.

We are going to take a wade in the shallow end of this before we dive deep.

For a compare and contrast example we have the anime version of Light Yagami from Death Note:

And his Americanized counterpart, Light Turner:

Both iterations of Light are characters that are defined by their intelligence. And both conform to the only tropes available to them because of this.

Yagami is popular and looked up to because of his intellect. He conforms to the Japanese trope of Top Student. He gets the best grades; he is socially adept and popular. He is also athletic. He is heterosexual and very attractive to girls, but he is in absolute control of his own desires regarding sex. He is at the top of the high school ladder. SSH rank: Sigma.

Turner conforms to the American stereotype of the nerd. He is highly intelligent and gets good grades but he is socially inept and unpopular. He is revered by no one. He is bullied by the “Chads” and ignored by the “Stacys.” When a girl finally does pay attention to him, he is instantly and completely at her mercy. He is at the bottom of the social totem pole. SSH rank: Gamma bordering on Omega.

There are no other high school tropes available to either boy. They just aren’t there for a male outsider character who is defined by his intellect. Neither Japanese or American society provides alternative tropes for the character of a highly intelligent boy who is an outsider.

In the East high intelligence must be venerated, it comes with built-in social status.

In the West it’s optional extra… At best.

These are just two examples of similar character traits inspiring drastically different tropes.

Let’s take a quick look at a trope that is native to the East. The leader and his Nakama. The protagonist and his team.

Each member of the Nakama corresponds to a known sub-trope. These are:

The Leader:

The protagonist, the guy whose story this is.

The Rival:

Another Alpha who wants to be in charge but respects the Leader enough to follow but not without frequent grumbling.

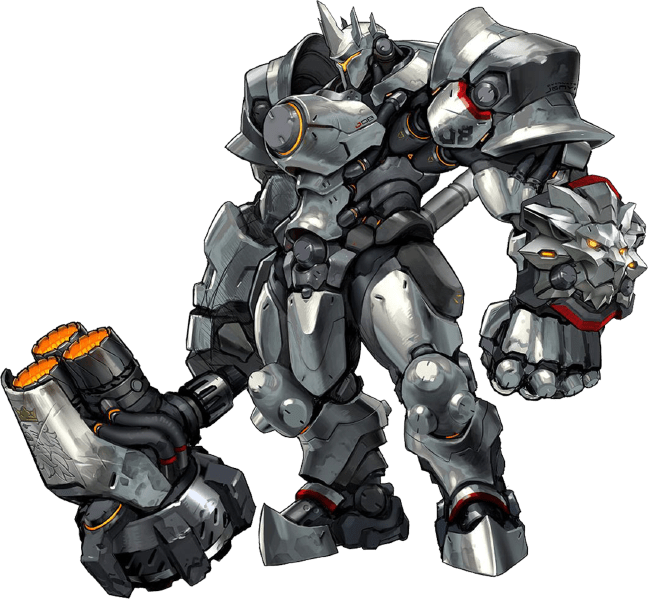

The Tank:

He’s the muscle. One of nature’s Bravo Males, he’s everyone’s best friend. Often he’s an older male. He is usually good for a hearty laugh and is often kind-hearted for all of his toughness. But can also be troubled and taciturn.

The Brains:

The engineer, the technician, the scientist, the advisor, the guy with the glasses. SSH rank: Delta.

And the Heart:

The healer, the comforting voice, and the hand holder. The glue that holds the Nakama together. And invariably, the Chick. The Leader and Rival often vying for her affection, however, this isn’t a requirement of Nakama.

Another sub-trope of Nakama is that enemies will frequently become friends and join the Nakama. In Guron Lagann, Viral was the enemy. After the original leader, dies and Simon steps up to take his place, Viral eventually joins Simon’s Nakama as his Rival.

Nakama is a trope native to the east but it isn’t too hard to find examples of hero teams in the West that fit the trope.

One of the reasons that the third Star Wars trilogy failed in China (aside from it being hot, burning garbage) is that there was no Nakama. The potential was there for one, but it never developed.

Least of all my friends.

The big reason that the Avengers took off in China was that its members conformed perfectly to the Nakama trope.

Gettin by with a little help from my friends.

Now on to the meat of the matter. Story structure itself.

Most of our fiction is based on the three-act story and conflict is central to this structure. All aspects of the tale will be adjacent in some manner to the central conflict.

Act I: Setting, we meet the characters and get to know their world, and the conflict is introduced. Act I ends when there is an inciting incident that begins the second act.

Act II: The tension of this conflict builds and escalates. Act II ends when the tension comes to a head.

Act III: The climax of the story; where one way or another the conflict is resolved and is no longer present. Tensions rapidly deescalate and the story slips into the (optional) denouement.

Conflict is essential to this story structure.

In the West, the struggle is external.

In the East the struggle is internal.

This is defined by the story structure Kishōtenketsu. Yes, that is a Japanese word but the same concepts very much apply to storytelling in the rest of the Far-East. Hell, China basically invented it with Journey to the West.

Kishōtenketsu is a compound word whose sub syllables describe their steps in the plot. Kishōtenketsu works like this:

Introduction (ki): introducing characters, era, and other important information for understanding the setting of the story.

Development (shō): follows leads towards the twist in the story. Major changes do not occur.

Twist (ten): the story turns toward an unexpected development. This is the crux of the story.

Conclusion (ketsu), also called ochi (落ち) or ending, wraps up the story.

I first took an interest in Kishōtenketsu when I was trying to find an answer to the question of; why doesn’t One Punch Man suck? How does it work so well when the hero of the story is so ludicrously over-powered that he can literally solve any conflict with a single punch? And the answer was that conflict while part of the story is never at the heart of the story. The real story of One Punch Man is Saitama’s lost humanity and his quest to regain it through the friendships that he forges with other superheroes. Frequently his story is told through the various members of his developing Nakama.

Ki: Saitama, the problem of his loss of humanity, and his world of superheroes are introduced. He has terminal ennui because he is the absolute physical apex and faces no challenge and thus cannot achieve anything. And his struggle to find just one enemy that will be a challenge to him is presented as central to his identity. His quest is to find just one enemy that he can NOT defeat with a single punch.

Shō: His journey as a hero begins when he is befriended by the cyborg Genos. He joins the Hero Association and starts climbing its ranks. Starting from the very bottom.

Ten: The all-important Twist. The apex of the story. The alien Boros invades the Earth. Boros has the exact same problem as Saitama. He has fallen into terminal-ennui as he has never met a single enemy he couldn’t defeat with a single punch. They fight, it’s extended and it’s epic. Saitama defeats Boros although Boros realizes that Saitama could have beaten him at any time with one punch. But Saitama took pity on Boros and dragged out the fight for a long time. Letting Boros achieve his dream, if not Saitama’s.

Ketsu: Saitama did this for the sake of another person. He has regained some of his humanity.

Let’s take another example that is better known in the West. Hamlet.

Act I: We find out what’s rotten in the state of Denmark. Inciting incident: Hamlet’s ghost dad orders him to kill his murderer who happens to be Hamlet’s usurping uncle.

Act II: Hamlet mopes around for three hours but he does build a lot of tension and finally accuses his uncle of murder in the most passive-aggressive way possible by having actors do it in a play within the play itself.

Act III: The climax. Hamlet has resolved to kill his uncle and Uncle King has decided to whack out his annoying, greasy little step-son. He recruits a guy who has good freaking reason to kill Hamlet. The hits get botched and most everyone dies. Hamlet makes another long-ass speech before he croaks.

Now let’s turn it into a Kishōtenketsu story by following it through the eyes of Hamlet’s best friend Horatio.

Ki: The setting is introduced. Horatio’s close friendship with Hamlet is established.

Shō: Horatio’s heart is joined with Hamlet’s on the prince’s journey into a near-psychotic break. He tries to come to grips with his duty and he suffers as Hamlet suffers.

Ten (The Twist): Hamlet fucks up his assassination attempt. Laertes dies (the poor bastard). Hamlet’s mother dies. Claudius dies. Hamlet is laying mortally wounded and Horatio breaks down at the sight of so much pointless bloodshed. He nearly commits suicide himself. Horatio achieves Enlightenment upon hearing Hamlet’s pleas to not kill himself if he ever had any love for him at all.

Ketsu: Horatio puts Fortinbras on the throne as his Prince instructed and then joins the priesthood (presumably).

Conflict was integral to Hamlet’s story.

Conflict while present in Horatio’s Kishōtenketsu version of these same events, was only incidental to his story of achieving Enlightenment. The fault lay in himself.

And Horatio overcame it.

I hope you enjoyed this quick survey of a very complicated subject.

Okay, I’m done here.

Thanks! One of the reasons that long-form storytelling took off in the West in recent years is, I think,because of the Eastern style of storytelling creeping into the culture. It’s hard to cram an entire Eastern story arc into 90 minutes. But if you have a movie trilogy (of 3 hour movies) or an entire TV series, then it becomes easier.

This is also why feminist-written adventure movies like nu-Star Wars tend to fall flat. In a movie with an oppressor-victim narrative, you can’t have nakama. You can only have the Brave and Powerful female characters and their male subordinates. Villains are males who have not learned to be subordinate and/or to recognize female supremacy.

LikeLike

You clearly don’t understand SJW’s narratives, you have to like the brave diverse characters because diversity and reasons.

Duh

LikeLike

I expected to enjoy learning from this post. I did not expect that I would be inclined to bookmark it for future reference.

This was an awesome post. And I really need to watch One Punch Man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reading this, I just realized why so many Eastern shows and anime start of with a monster of the week structure to introduce the heroes and give them something to do while building up to the twist and main conflict.

LikeLike

Oh my god! The man can be taught!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! That is a great explanation.

You have a gift!

LikeLike

Thank yoiu.

LikeLike

Great post!

LikeLike

Now you’ve done it, Cataline. This is already my favorite post on your blog for the year 2020. Can you top this sometime in the next eight months?

LikeLike

Is there any chance you could tackle an explanation/exposition of humor of West vs East/Japan?

That being: Western humor: Setup (short to medium length), Punchline (short).

Versus the Japanese structure of: Punchline first (rather long), then Setup (not really needed, but there).

A recent example out of Japan being the recent(-ish) movie “One Cut of the Dead”

LikeLike

Humor in different cultures is a much more difficult subject because it’s so difficult to quantify.

There are some definite things I am aware of. In Japan the pun is still highly prized as an art form. In English speaking world we just groan but that didn’t used to be the case. In Shakespeare’s day puns were highly prized and his plays are loaded with them.

No idea why that changed and no way to know.

LikeLike

Thanks.

I think one reason that then is so prized in Japan is that it’s about the only form allowed by common culture.

For example, a Don Rickles styled comedian dishing out “personal insults”… absolutely verboten. In the same vein, and less intense, using “biting remarks”… a non-starter. Add to that, “sarcasm”… doesn’t register here… at all.

I think the “personal insults” embargo may have been the Shakespearean issue. To appeal to a wide audience, the target would have to be a well known figure (say, The Monarch), which wasn’t as well tolerated as today.

LikeLike

Oops, wrong link:

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7914416/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

LikeLike

And I forgot to ask, where how did you come to gain such an in-depth understanding of things Eastern virus Western?

LikeLike

Trust me, this isn’t that deep at all. I just looked at a few things differently is all.

LikeLike

*versus*

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person